By Carley Goodreau

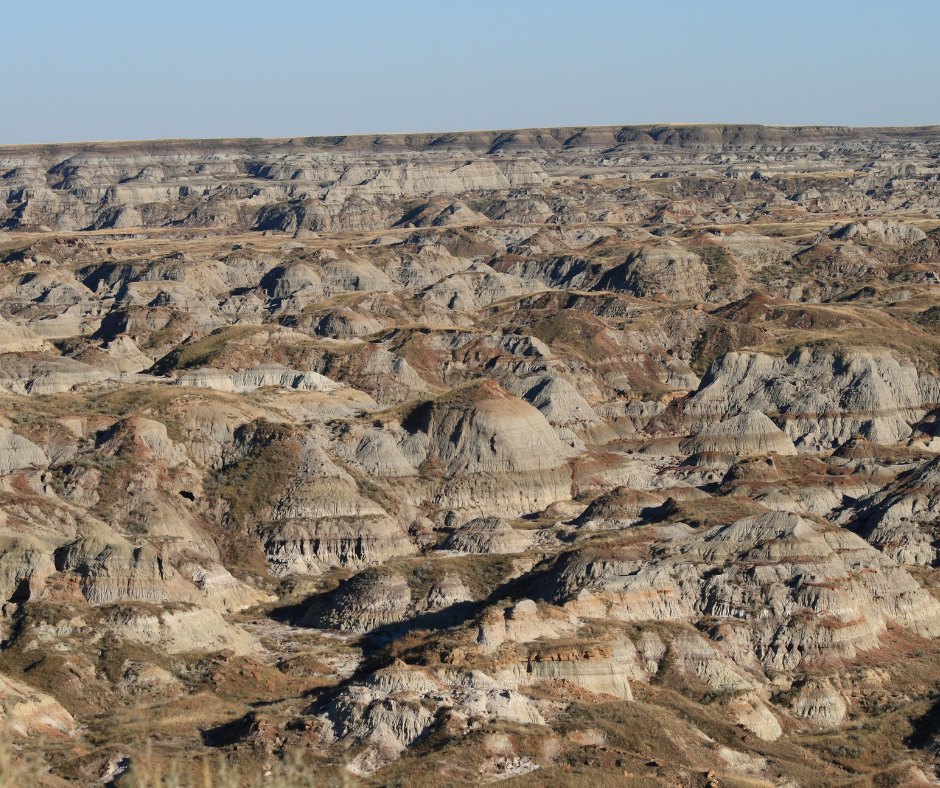

The Lakota people first called them Mako Sica – directly translating to “bad lands,” the French: “les mauvaises terres a traveser,” – bad lands to travel across.1 The rough and winding terrain make finding your way difficult, and the climate (exposed, temperatures on either extreme, lack of water) do not provide a comfortable environment for people.1

Badlands are regions that have many exposed layers of soft rocks and clays, like limestones, sandstones and shales.2 Over time, ice, wind, and water eroded the layers to create the hoodoos, ridges, crevices, caves and gullies so familiar to the badlands landscape.3 These areas are naturally occurring, and contain many fossils, including dinosaurs. Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, a UNESCO heritage site, is home to the largest stretch of badlands in Canada. 3

The badlands are constantly changing, further eroding under the same forces that carved them, building up deposits of sediments during times of rain and flood, drying out again and creating new cracks and crevices. At first glance, the badlands appear hostile – dry, barren, cracked and dusty. Look closer, and you’ll see this unusual landscape teeming with life.

Imagine you are a bird, soaring high above the prairie of Southern Alberta, the green and gold fields stretching out in every direction before you. Almost unexpectedly, the earth cracks open into a wide valley. Beige cliffs plunge down to rocky ravines, and lines cut horizontally – the separation of each layer, each a different shade of grey and brown. Little vegetation is present, mostly low lying, drought resistant shrubs can make it here.

Dip down into the valley and look to the cliff faces high up on the buttes and hoodoos. In crevices set back into the rock to protect from predators, but close enough to the surface to retain heat from the sun, small-footed bats make their roosts.4 In the winter, these little bats, with feet just one centimeter long, will hibernate deeper into crevices. 4 The western small-footed bats prefer rocky roosts and will fly out to insect dense areas near bodies of water to feed.5 Their fur is a light tan colour, making them almost indistinguishable from the surrounding cliffs. A group of up to six female bats are in a crevice together, using the sheltered area as a maternity roost, to give birth and raise their offspring.5

Continuing to fly through the valley, you swoop under the overhang of a cliff and past many nests made of the ample mud available in the badlands. Clustered together, they almost look like pottery jugs stuck to the cliff wall. A cliff swallow flits into the mouth of a nest.6 Its bright brown throat stands out, but its elevated perch protects from predators.7 With the jagged appearance of the cliffs, you could easily fly right by without noticing the nests.

Glide down to the rocky canyon floor and you’ll see low lying vegetation and perhaps a drought loving flower or two. A tiny bird hops along the ground, fishing insects and spiders out of cracks in the ground with its thin, long beak.8 Its short wings rustle as it hops, making the most of its foraging grounds. Rock wrens, lovers of arid, rocky environments, prefer areas of sparse vegetation and gain all the moisture they need from their insect-based diet.9 Later, in the heat of the day, the rock wren will retreat to the shade to rest or forage further. It nests in between rocks or in crevices and will build a “front porch” made of tiny stones to mark the entry way to the nest.8

Weaving over and around the craggy landscape, you feel the warmth of the sun beating down. Further up on a rock, so does a rattlesnake, basking in the warmth of the rays. Its light tan and brown colouring, and blotchy pattern camouflage him against his surroundings.10 Rattlesnakes are common in badlands and similar habitats, relying on shrubs and rock for cover. The badlands make a perfect habitat for snakes, as they use burrows and crevices for cover, spending winters in a communal den.10 Rattlesnakes eat primarily small rodents and have heat sensing pits on their faces that help them locate their prey.10 Rattlesnakes are distinguishable from other snakes by their triangular shaped head, and more importantly, the rattle on the end of their tail. The distinctive rattle sound is used to warn other animals approaching to stay away; it only bites if it is threatened.10 Today, however, the rattle is silent, and you fly on.

Big, round ears and long bushy whiskers identify a woodrat scurrying along the canyon floor, its bushy tail curled behind it. Busily collecting debris for its nest, the woodrat, also known as a pack rat, will drop what it is carrying for something new or shiny.11 These rats are native to Alberta, and make good use of the landscape as they love to build nests, once again, in rocky crevices. 11 They strengthen their nests by using urine to harden it.11 Their diet consists of a diverse range of foliage, seeds, and fungi.11 Woodrats build caches of food, which sustains them through the winter as they do not hibernate. The woodrat carries on, industriously packing its supplies away in the safety of its crevice.12

As you soar upwards, the canyon becomes once again a vast expanse of rock and clay, hiding the activity that pulses within it. Housing both predator and prey, feeding, protecting, and camouflaging, the badlands make a great home.

References

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/mako-sica.htm

- https://naturealberta.ca/bad-but-beautiful/

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-are-badlands-and-where-do-they-occur.html

- https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/e50f0e03-3a62-4b2d-a2d9-3d84ce813fe5/resource/8cc1365d-d259-45a9-9a58-fc342cf5f51d/download/sar-westernsmallfootedbat-consmanplan-2012-17.pdf

- https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Myotis_ciliolabrum/

- https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/cliff-swallow

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/birds-badl.htm#:~:text=In%20summer%2C%20insect%2Deating%20cliff,offs%20provide%20protection%20from%20predators

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Wren/id

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Wren/id

- https://canadianherpetology.ca/species/species_page.html?cname=Prairie%20Rattlesnake

- https://fieldguide.mt.gov/speciesDetail.aspx?elcode=AMAFF08090

- https://animalia.bio/index.php/bushy-tailed-woodrat