By Sydney Nelson

Birds are ubiquitous on Earth: they inhabit every continent and every ecosystem, from tundra to desert and wetland to rainforest. In Alberta alone, we have almost 500 different species of birds (Museum n.d.). Birds are incredibly diverse, but they all share a few adaptations that other extant vertebrates do not have: They all have beaks and wings, and though not all of them can fly, they all have feathers. Feathers have evolved for approximately 235 million years (Viegas 2009) and primitive feathers looked very different from what we see on modern birds today. Extinct dinosaurs primarily used their quill-like feathers to attract mates, but birds today use them for many different functions. At AIWC, we treat birds that utilize their feathers for temperature regulation, waterproofing, and flight.

What are feathers?

Like our fingernails and hair, feathers are primarily made of keratin. All feathers have a central shaft with pairs of hooked barbs branching from it (Britannica 2023), and the hooks help the feathers keep their smooth shape. The feathers of a peacock’s tail look very different from the downy feathers of a baby robin, but the basic structure is similar.

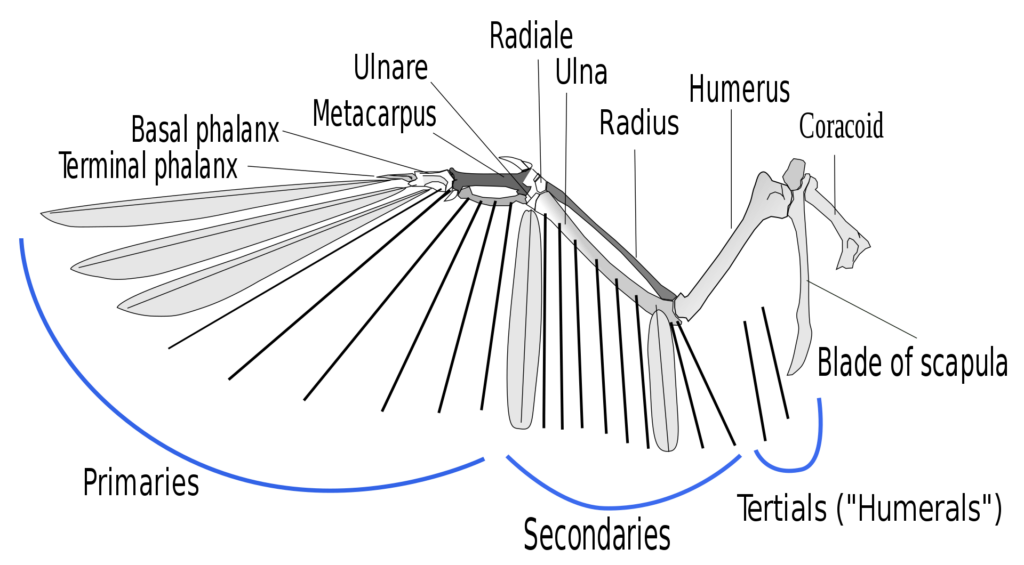

There are three types of feathers found on the wings of modern birds: Primaries, which are the largest; secondaries, which provide lift when the bird is in flight; and tertials, which cover the primaries and secondaries for protection when the bird is not in flight (Currie n.d.). The tail feathers are called retrices, and they help the bird maneuver through the air with controlled precision, like the rudder on a boat.

Bones of bird wing. Image licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5, by L. Shyamal [link]

Altricial vs. Precocious Babies

Have you ever wondered why some baby birds are born featherless with their eyes closed, and others hatch already covered in down? Altricial birds are born naked except for scarce patches of downy feathers, and they cannot leave the nest until they grow their juvenile feathers, which have a stick-like appearance at first. They rely on their parents for warmth and food. Precocious babies are born fluffy and ready to leave the nest within one or two days of being born, walking and swimming with the supervision of their parents. Some birds, like owls and hawks, are covered in downy feathers at birth but remain with their parents until they can independently fly and feed themselves (Report n.d.). Knowing the differences between altricial and precocial birds can help determine whether a baby bird on the ground needs help.

Altricial American robin chicks (left) and precocial Canada goose goslings (right). All patients cared for at AIWC in 2023.

Moulting, Waterproofing, & How We Help

A couple of processes pertaining to a bird’s feathers can leave them vulnerable and in need of assistance from places like AIWC. The process of shedding and regrowing feathers is called moulting. Usually, it happens because the bird will display a different type of plumage based on seasonality or because the feathers are damaged and must be replaced. Bald eagles, for example, do not moult into their iconic “bald” look, complete with beak and eye colour change, until they are around three years old (Society 1989). Male Mallards, or drakes, lose their instantly recognizable green head feathers for a more neutral look for several months per year, which is called their “eclipse” moult (Takamado 2021).

Many birds cannot fly while they moult, rendering them more vulnerable to predators (Volunteer 2023). Late this summer, AIWC admitted a Kestrel from B.C. with her feathers severely damaged by the wildfires. Unable to fly, she will remain in care until she moults completely, likely in the spring of 2024. In the meantime, she will be able to recover safely.

AIWC can also help water birds with their feathers by encouraging them to waterproof themselves effectively. To become waterproof, birds need to preen, spreading oil throughout their feathers and then zipping the feathers together to create a barrier between their bodies and the water. AIWC helps by alternately giving the birds time in water and time spent with warm air blowing on them, encouraging them to preen.

If you would like to help us care for our feathered friends, there are many ways to get involved, including symbolically adopting an animal, visiting our store, or volunteering with AIWC.

Bibliography

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. 2023. Feather. September 16. Accessed October 22, 2023. [link]

Currie, Phillip J. n.d. Paleontology: Theropod Dinosaurs and the Origin of Birds. Accessed 08 06, 2023. [link]

Museum, Royal Alberta. n.d. Official List of the Birds of Alberta: Taxonomy. Accessed October 21, 2023. [link]

Report, Avian. n.d. Altricial or Precocial Young Birds: Know the Differences. Accessed October 2022, 2023. [link]

Society, Wilson Ornithological. 1989. Molting Sequence and Aging of Bald Eagles. March. Accessed October 22, 2023. [link]

Takamado, HIH Princess. 2021. The Eclipse Moult of Mallards. December 16. Accessed October 22, 2023. [link]

Viegas, Jennifer. 2009. Earliest feathers were for show, not flight. January 12th. Accessed October 21, 2023. [link]

Volunteer, AIWC. 2023. Moulting Season: Why Waterfowl Don’t Fly in Summer. March 14. Accessed October 22, 2023. [link]